Your donation will support the student journalists of Tunstall High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

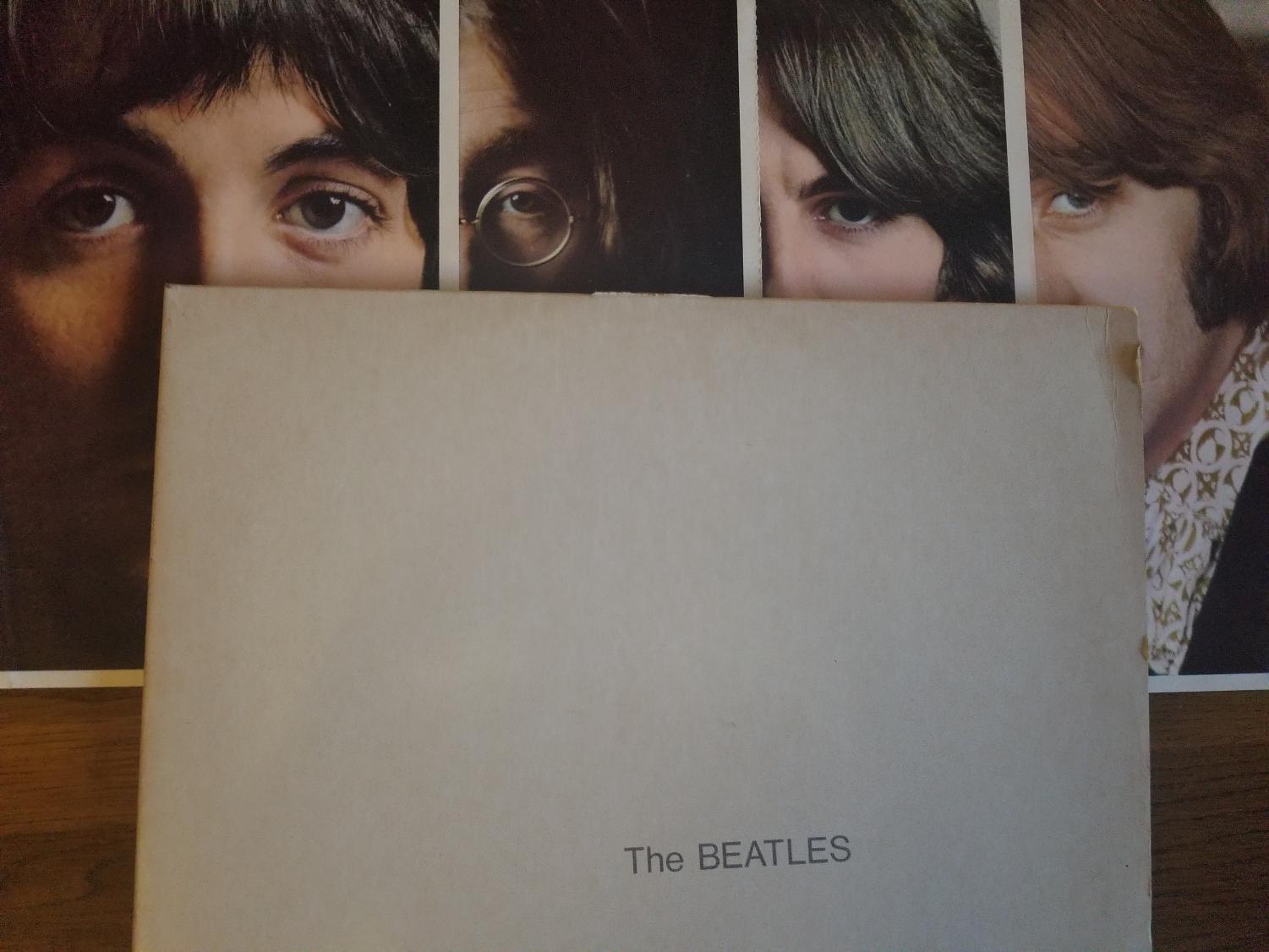

The White Album: Deconstructing the beginning of the Beatles’ end

September 13, 2018

It’s May of 1968, and the greatest rock band to come out of Liverpool are at the verge of tearing out each others’ throats. Paul McCartney forces the band through grueling takes of songs that only he really likes. John Lennon, recently attached to Yoko Ono, the performance artist who had stolen his heart years before, finds himself in a deeper pit lyrically than he had ever been before. George Harrison and Ringo Starr, however, start to put a space between the other two, finding the infighting and bickering to be all too much.

What came out of this?

The best album the band ever released.

The Beatles’ The White Album is a stunning accomplishment of a record that very nearly rendered the band dead in the water. It has mountainous peaks, and stark, depressing valleys. It’s what Lennon himself described as “the sound of a band breaking up.”

It’s a mess.

Songs crash into one another, fragments of songs improvised in the studio are tacked onto each other, various bits of chatter from band members and engineers can be heard here, there, and everywhere. This is not to its detriment, though.

The appeal of this album is finding the diamond in the rough.

For every “Back In the U.S.S.R.,” there is a “Wild Honey Pie.” For every “Julia,” there is a “Revolution 9.” For every show-stopping radio tune or beautiful ballad, there’s an equivalent song that feels like a throwaway, an afterthought.

One of the more apt descriptors of this monster double album is that it sounds and flows like three solo albums trying to fit under the same roof. Paul, George, and John couldn’t compromise on who got less and who got more, so they decided to fill four sides, two records, with everything they wanted. This gave them room to breathe after feeling strangulated, first by touring, then by whittling down tracklists to be fair and maximize revenue at the same time.

Paul decided to go with what had worked before. He pastiched other artists with songs like “Back In The U.S.S.R.” He continued his trend of making “granny music,” as John said, with songs like “Honey Pie” and “Martha My Dear.” He got political and minimalistic with “Blackbird.” He may or may not have prototyped metal (and instigated a cult) with “Helter Skelter.” After years of cultivating a ‘team player’ image, Paul managed to finally craft an image of himself that was entirely ‘his’: the tough one; the lovesick troubadour; the leader of the band.

John, seemingly jumping at the word experimentation, went some places that he had never dared to beforehand. To give an example of his range, he fashioned an unwieldy progenitor of avant-garde sound collages with “Revolution 9,” and conversely used just a Travis-picked acoustic guitar to create the single Beatles track with only his work on it: “Julia,” a flooring ode to his late mother and his soul love, Yoko Ono. His breakthrough, though, was ironically the first song that he recorded with the band for the album. “Revolution” is the Lennon manifesto. It is Lennon crystallized. It’s sharply political, it’s quick-witted, it’s relaxed and lowkey, and it’s the distillation of Lennon’s entire public persona into a bluesy jam-session.

Ringo Starr, born Richard Starkey, was never a confrontational type when it came to music. Ringo was the backbone of the band; the drummer they relied on most. He even felt uncomfortable recording the last high note on his solo song on Sgt. Pepper, “With A Little Help From My Friends.” Ringo’s place was to back up his friends. Maybe then, Ringo was the canary in the coal mine of the band’s break up. In mid-October, Ringo left a recording session, said he was quitting the band, and didn’t return to the studio until early September. Ringo Starr, the left-handed one who had the goofiest air about him and always had some way to augment his back beat to fit the others’ songs, had been so torn down about the standards to which he played drums that he left the band that defined him for weeks on end. When he returned, George Harrison, the one whom Ringo felt closest to, had decorated his drum kit with flowers.

George Harrison had always been accused of being ‘the quiet one.’ Seemingly, though, he just wanted to conserve what he said and did to make his actions more impactful. His true personality lies somewhere between these two. George’s contributions to The White Album showed his eloquence and his flair for showy musicianship. “Piggies” is George’s sharp stab to materialism and capitalism, and the voice he employs through this song shows the Animal Farm-like concealment of true motives. “Long, Long, Long” is the continuation of his spiritual journey, and almost feels like the sigh at the end of a long sentence, as George finally comes to terms with the god he was chasing. The most interesting story to come from the ‘quiet one’ is the story of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” though. George was seemingly unhappy with the performance of his bandmates in the initial recordings of the song, and decided that to shape the other three up, he needed to bring in a more seasoned craftsman to solo on a track. Who, then, would that be?

Eric Clapton. The Eric Clapton.

“While My Guitar Gently Weeps” is not only the standout track from the album as a whole, but a major personal accomplishment for Harrison. This was the song that catapulted him to the spotlight before “Here Comes the Sun” invaded everyone’s turntables in 1969. Harrison had defined himself fully and truly this time around, no longer riding the coattails of Lennon-McCartney.

All things considered, The White Album may not be their best in a classical sense. It is, though, the Beatles in their most unrestrained and creative. Really though, nobody knows what got this album through the constant bickering. Every time the band fought, it seemed closer to the end. What was the secret to this album?

Maybe it was the tension. Maybe it was the anger. Maybe it was the isolation.

Whatever it was, the resulting product was well worth the struggle and fighting.

Emily • Sep 13, 2018 at 11:53 pm

I absolutely love this. Great article, Cam